THE HISTORY OF CARVERS GAP AND ROAN MOUNTAIN

From the time the first Native Americans visited Roan Mountain by way of Carvers Gap, to the modern day hiker.

Carvers Gap has played a prominent role in the history of The Appalachians and our Country.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, botanists paid frequent visits to the area to collect plant specimens.

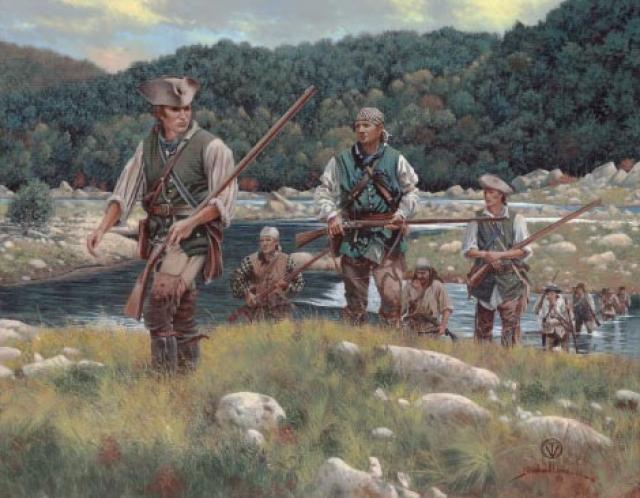

In 1780, at the height of the American Revolution, a group of frontiersmen known as the Overmountain Men, crossed the Roan Highlands en route to engage and defeat Major Patrick Ferguson’s forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain.

In 1826, Josh, Ben, and Jake Perkins noted deposits of iron ore near Cranberry Creek which led to the discovery of a massive iron ore deposit known as the Cranberry vein and the establishment of the Cranberry Mine .

In the late 19th century, the logging industry was booming and Roan Mountain was no exception.

Ever since the mid 19th century, tourist have been visiting Roan Mountain by way of Carvers Gap.

Recreational use of the Roan Highlands has changed significantly over the years. Despite changes in the management of the area, the Roan Highlands have remained an icon for the states of Tennessee and North Carolina for decades. Famous political figures, frontiersman, industrial tycoons, and botanists have frequented the Roan. While these explorers made important scientific discoveries in the Roan Highlands, the Native Americans, namely the Cherokee, were the first people to step foot in the area. The Native Americans may have used the balds for agricultural or hunting purposes, but there is no evidence of their creating permanent settlements on the balds.

THE BOTANISTS

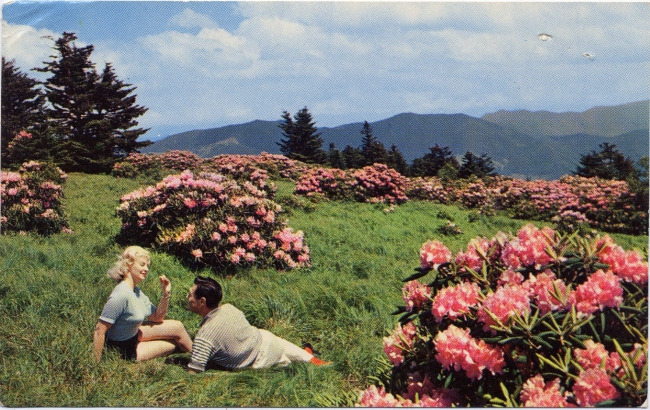

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, botanists paid frequent visits to the area to collect plant specimens. Among them were John Bartram, who crossed the Roan Highlands in the late 1730s while studying the botanical make-up of what is now the southeastern United States. Andre Micheaux followed in 1794, discovering several alpine species rarely found outside of the New England and Canadian latitudes. A few miles into western North Carolina is the Catawba River where in 1796 Andre Michaux found the rhododendron species he named catawbiense after the river. In 1799, John Fraser explored Roan Mountain, collecting specimens of rhododendron and noting the existence of the evergreen fir tree native to Roan that now bears his name. Other early explorers included Elisha Mitchell, for whom Mount Mitchell is named, and Harvard botanist Asa Gray is the namesake for the Roan’s most famous flower,Gray’s Lily

.

Some of the biodiversity in the highlands

Known as The Highlands of Roan, these mountain peaks and ridges, for the most part above 4,000 feet in elevation, are renowned for their exceptional biological diversity and magnificent beauty.

The Roan Highlands are home to grassy balds, rhododendron gardens, high-elevation rock outcrops, and rich spruce-fir forests. The Roan’s ecosystem is one of the richest repositories of temperate zone biodiversity on earth, including more federally listed plant species than the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Roan Highlands are home to more than 800 plant species and over 188 bird species

ANDRE MICHAUX

JOHN FRASER

ASA GRAY

THE

OVERMOUNTAIN

MEN

In 1780, at the height of the American Revolution, British General Charles Cornwallis opened his invasion of the southern colonies with the capture of Charleston, South Carolina and a victory over American forces at Camden. With South Carolina apparently secure, Cornwallis marched north toward Charlotte, North Carolina. During this march, Cornwallis dispatched a band of Loyalists under the command of Major Patrick Ferguson to raid Western Carolina.

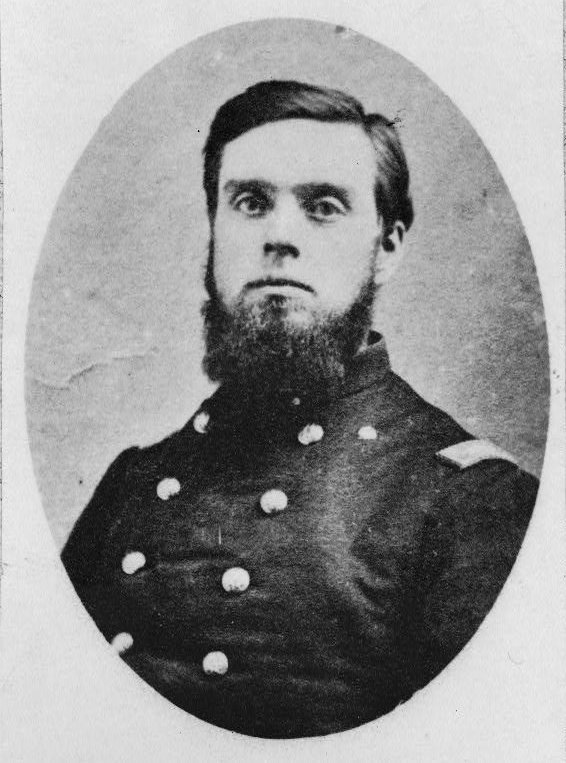

To counter Ferguson’s threat, the militia leaders—including colonels Isaac Shelby, Samuel Phillips, John Sevier, William Campbell, Arthur Campbell, Charles McDowell and Andrew Hampton—assembled their troops on the Watauga River at an outpost called Sycamore Shoals.

Minister Samuel Doak said unto the gathered troops, “The enemy is marching hither to destroy your homes.…Go forth, then, in the strength of your manhood to the aid of your brethren, the defense of your liberty and the protection of your homes.”

This rallied force of frontiersmen — known as the Overmountain Men — crossed the Roan Highlands en route to the other side of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where they engaged and defeated Ferguson’s forces at the Battle of Kings Mountain. While most returned home afterward, some Overmountain Men continued southward to link up with Daniel Morgan’s forces and contribute to the American victory at Cowpens in 1781.

.

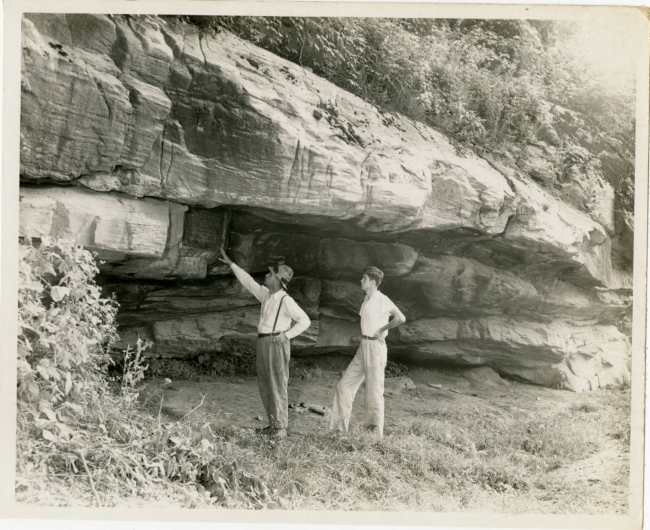

Prior to the Revolution, very little gunpowder had been made in the United States. During the colonial period, most gunpowder used in America had been manufactured in Britain. In October 1777, the British Parliament banned the importation of gunpowder into the rebellious American colonies. To supply the Overmountain Men, five hundred pounds of black powder was manufactured by Mary Patton and her husband at their Gap Creek powder mill in present-day Elizabethton. On the first night of the march from Sycamore Shoals, the Overmountain Men stored the Patton black powder in a dry cave known as “Shelving Rock” to protect it from the rain. Shelving Rock is located along TN-143 just outside Roan Mountain State Park

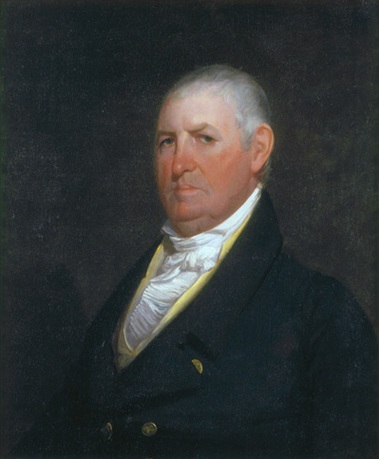

ISAAC SHELBY

JOHN SEVIER

SAMUEL DOAK

THE INDUSTRIALISTS

Mining and it’s influence

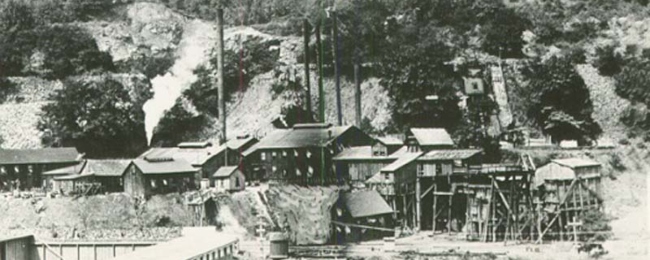

In 1826, Josh, Ben, and Jake Perkins, three brothers from Crab Orchard, Tennessee were searching for ginseng on the North Carolina side of Roan Mountain when they noted deposits of iron ore near Cranberry Creek. This led to the discovery of a massive iron ore deposit known as the Cranberry vein and the establishment of the Cranberry Mine, which extracted the ore for nearly a century until being forced to close by the Great Depression.

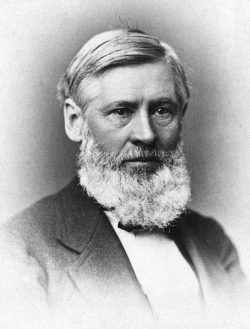

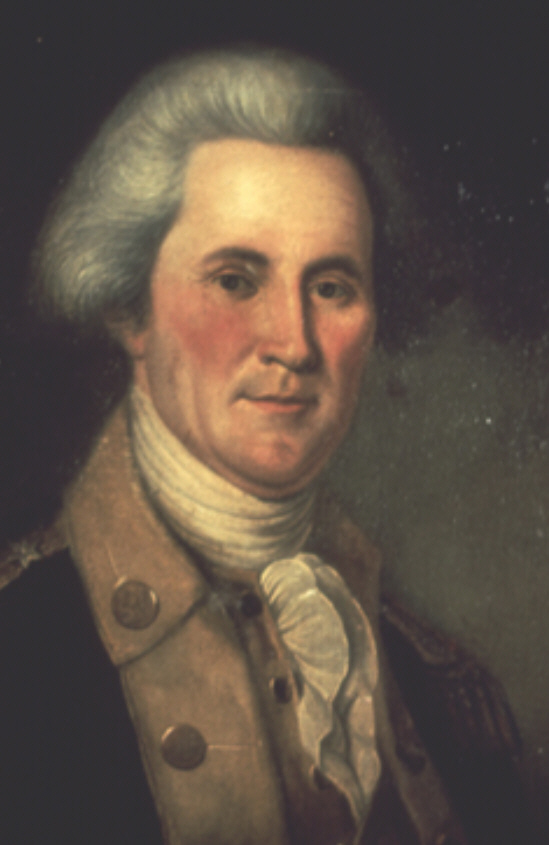

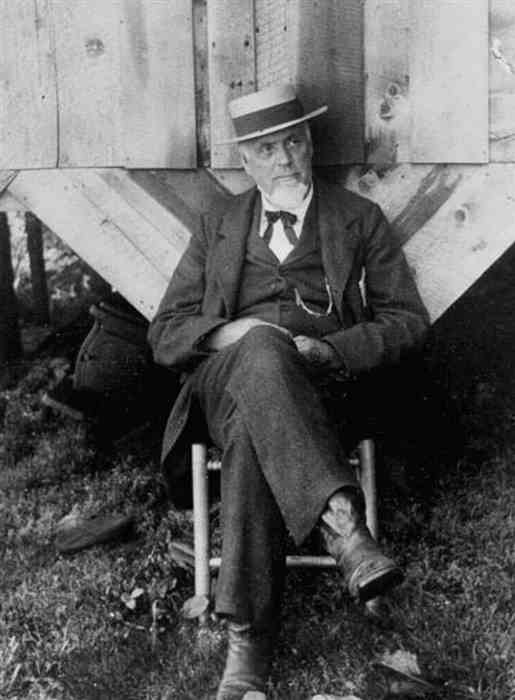

John T Wilder purchased a portion of the Cranberry Mine just over the border in North Carolina a few miles from Roan Mountain.

As Wilder investigated other parts of Tennessee in his pursuit to find new suitable locations for his mines he went to Johnson City, in the northeast corner of the state. There he found an area in which he could bring together the iron ore of North Carolina,and the coal of Virginia and Kentucky. Nearby was Roan Mountain, one of the highest mountains in the Appalachian Mountain range, and it reminded him of his boyhood home in the Catskill Mountains of New York. He purchased the land on the sides and top of the mountain in 1870 at the cost of fifty cents an acre whereas the land he purchased in the valley went for $25.15 per acre. Over the next few years he built a small house, to which he constantly added rooms, to accommodate the steady stream of friends and family that came to visit. By 1877 he was taking paying guests at what turned out to be his first hotel on the mountain.

At Roan Mountain Wilder found huge deposits of magnetite. There were already beehive iron furnaces at nearby Buladean and the Cranberry furnaces at the northeast end of the mountain, just inside North Carolina. Whereas the ore from his Rockwood TN furnaces contained too much sulfur, which produced a too brittle iron for train rails and wheels, the Cranberry ore was sulfur-free. Transporting this ore from Roan Mountain down to the Nolichucky River on to Rockwood via the Tennessee River proved to be too expensive.

Hence a narrow gauge railway was added. By 1882 the East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad carried the Cranberry ore to Johnson City by way of Roan Mountain. This also enabled passenger access to the top of Roan Mountain from the Tennessee side. The narrow gauge line know as Tweetsie Railroad or the Railroad with a Heart still operates with engine #12 in Blowing Rock NC as an amusement park.

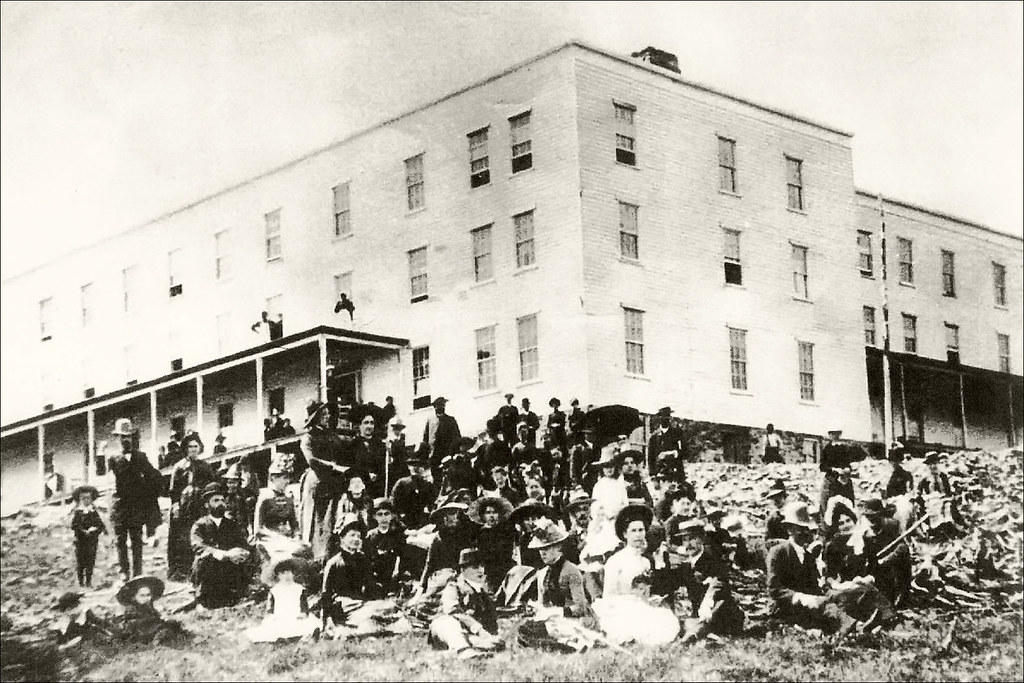

This allowed Wilder to build a home, inn and luxury hotel at the top of the mountain. By 1885 this hotel, the Cloudland Hotel, had one hundred and sixty-six rooms (and supposedly one bathroom!). The top of the mountain had long been referred by locals as Cloudland, after the clouds that often obscured the peak. People came from miles around and found, because of its high altitude at 6285 feet, that it gave relief from hay fever. The rates were $2 a day, $10 a week, or $30 for four weeks. The Cloudland Hotel was heated by steam, still uncommon in that day. A spring eight hundred feet below the top supplied the water, which was delivered via hydraulic units which filled tanks next to the hotel. There was a golf course, croquet grounds and a bowling alley. A doctor, butcher, baker and barber were all available. Wilder advertised both nationally and internationally. One advertisement for the hotel stated: “Come up out of the sultry plains to the Land of the Sky- Magnificent views where the rivers are born. One hundred mountain tops over 4,000 feet high, in sight.” The Cloudland Hotel straddled the Tennessee-North Carolina state line and it was said that some guests could sleep with their bodies in two different states. A line was painted in the middle of the hotel so guests would know which state they were in. This may have served a practical purpose: Liquor was legal in Tennessee but illegal in North Carolina.

Here the Wilder family gathered in large numbers, along with countless friends, neighbors, scientists, and visitors, and these gatherings were happy occasions. The expense of maintaining a hotel such as the Cloudland for a short holiday season (because of its high altitude) proved to be its undoing. Wilder eventually hired managers for the hotel and not all were scrupulous in their care and spending. It began to decline in the early 1900s and was abandoned in 1910. The locals took to ransacking the hotel and within a few years the Cloudland was rapidly decaying. Wilder sold the property and the new owner began selling off items room by room. Wilder purchased a home in Johnson City, and became Vice-President of the Charleston, Cincinnati, and Chicago Railroad, later to become the Carolina, Clinchfield and Ohio Railroad. In 1892 he organized the Carnegie Iron Company in Johnson City, which he sold in 1897.

.

The Cranberry Mines NC 1932

Logging and the repercussions

In the late 19th century, the logging industry was booming, due in large part to the arrival of the band saw and the logging railroad. As forests in the lower lands were cut down, loggers began moving into the more mountainous areas in search of timber. At Roan Mountain, a steam engine was set up in the gap between Round Bald and Jane Bald (this gap is still called “Engine Gap”) to move lumber from the Tennessee side to the mills located on the North Carolina side. A large log flume was built between Burbank (near Hughes Gap) and the village of Roan Mountain. Erosion brought about by excessive logging was believed to be part of the cause of a massive flood that destroyed much of the area in 1901.

The Cloudland Hotel

GENERAL JOHN T WILDER

circa 1940’s

Roan Mountain, Tennessee

The original Cloudland Hotel

JOHN T WILDER

General Wilder and Family at Cloudland

Tourism since the

Mid 1800’s

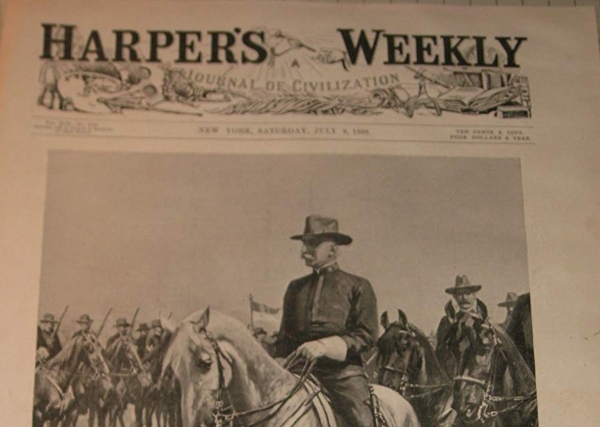

Tourists had been visiting Roan Mountain since the mid-19th century. In 1857, two such tourists recalled their visit to the mountain in an article written for New Harper’s Weekly:

The sweep of the vision in every direction is unlimited, except by the curvature of the earth or the haziness of the atmosphere. The first idea suggested is that you are looking over a vast blue ocean, whose monstrous billows, once heaving and pitching in wild disorder, have been suddenly arrested by some overruling power

A view of Carvers Gap and Roan Mountain in the distance. Taken in 1938

Having a Picnic on Roan Mountain 1947

Miss Virginia Hubbs (right), Martha Ruth Lady and Henry Brown Baker – all from Greeneville, Tenn., with an automobile, on top of Roan Mountain. 1940

1898 New Yorker Beats Summer Heat with Sojourn at Roan Mountain’s Cloudland Hotel

Around the end of the 19thcentury, northerners beat summer heat and annoying flies by vacationing in the relaxing pristine southern mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina, known as the “Land of the Sky.”

In early July 1898, H. T. Finck, a New York resident, traveled to Roan Mountain on a mountain railroad that traveled over what he deemed the “Cranberry Road.” The 40-mile long million-dollar endeavor was fabricated to transport steel. It picked up Mr. Finck at the Southern Railroad in Johnson City and chugged along toward his anxiously awaited destination.

After disembarking at Roan Mountain Station, he took a 12-mile stagecoach ride that was often used in tandem with trains to the top of the mountain at 6894 feet above sea level. Had Finck made the journey a couple of weeks earlier, he would have witnessed the stunning Catawba rhododendrons in full bloom.

The Cloudland Hotel was the tallest building east of the Rocky Mountains. The state line, dividing North Carolina from Tennessee, passed through the dining room where guests could cut their steak with a knife in one state and eat it with a fork in the other. Also, the rooms were situated such that guests could sleep with their head in Tennessee and their feet in North Carolina.

The building, capable of handling several hundred guests, exposed its broad sides gallantly to the violent winds without using chains anchored to stones like other mountaintop hotels. However, the roof of the Cloudland Hotel collapsed during high winds on two occasions forcing the owners to moor it with heavy rocks. A supreme test of strength occurred in July that year when a violent storm raged for three days nonstop. Although it was the fiercest squall the proprietor remembered in several years, the hotel remained firm on its foundation.

Weather was ideal in summer months with the thermometer dropping to 40 degrees at night, prompting the staff to burn huge logs in all the chimneys. The fires were kept lit day and night for those who desired extra warmth. During the day, the temperature varied between 58 and 64. The hotel was perfect for authors who could work at their trade and simultaneously enjoy the spectacular surroundings. Food in the dining room was not only reasonably priced but also quite succulent.

The hotel was aptly named because clouds afforded the best entertainment when they were not so close as to obstruct the view, as was often the case. The frequent rain that bathed the area usually vanished as quickly as it arrived. Air dampness was exhilarating, not depressing. Just below and behind the hotel was a ravine from which mists formed perfect circular rainbows by the setting sun. Sunsets were magnificently varied and beautiful, painting the majestic sky in all directions.

On some of the mountaintop balds, farmhouses of local residents could be observed. A few curious visitors became acquainted with some of them, whom they described as being perfectly “civil and safe,” except for their curious habit of feuding with nearby families like the stereotyped Hatfield-McCoy feud 20 years prior.

The inhabitants owned sheep, cattle, horses and pigs. Mr. Finck interestingly noted that, while the razorback pig was not an attractive animal, it lived a fresh air life, was fed on unspoiled grass and was bathed daily by unpolluted rains. He reasoned that this was why the animals yielded such well-flavored hams, humorously noting that the critters would stampede down the hill at the mere mention of salt.

A Cloudland Hotel, Roan Mountain stay over around 1900 was truly a wilderness paradise for visitors wanting a break from life’s demanding routines.